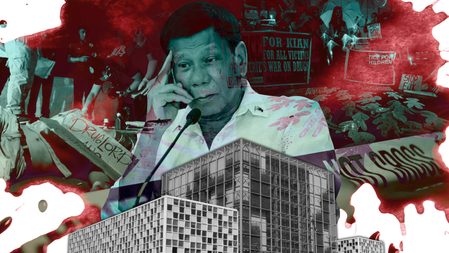

Duterte’s case being as much a judicial as a political one, therefore not going away soon, especially with his cultish cronies and followers, the long road to The Hague only bears repeating

When Rodrigo Duterte was arrested in Manila Tuesday last week and flown on the same day to the International Criminal Court, in The Hague (the Netherlands), the news was reported as though it were something unexpected, occurring in a vacuum, if you like, with no known cause or reason or antecedents.

The timing may have been unexpected, but certainly not the arrest and extradition. An ICC trial for Duterte had been a long-standing prospect, awaited or wished away, depending on where your sentiment lay. In any case, where one stands on the issue is beside the point; for the ICC, it’s the facts and the law that ultimately decide Duterte’s fate.

The news media presumably understood that. In fact, their effort was so concentrated on finding the facts, seeking out sources who knew, firsthand or officially, what was going on, that the air was left open to be exploited by partisans motivated by self-interest, anxious to sway the public to their sides.

An effective official blackout having been imposed as the news came to pass over more than 10 hours, about all that became known factually was that Duterte had been arrested and that a chartered plane had been sitting on the tarmac waiting to fly him away. With scarcely anything to go by except random feeds by mobile phone without context from people at the scene, radio, television, and online reporters and anchors could only fill the air with more air.

As a result, audiences genuinely looking to be truthfully, meaningfully informed were not helped, while the biased ones only became more entrenched in their biases. In other words, the press, the institution relied upon to sort things and set them right for the public, fell short.

In due course, legal experts and political analysts were enlisted, but they could do little to clear the air, for by then the air had become too thick, mostly with utterances obviously one-sided or fraudulent or even malicious. Much of those utterances could have been blocked out or at least minimized or neutralized. A retracing of the long road to The Hague, the chain of antecedents leading there, would have done nicely instead; it would have provided the context to the news, to what little of it that had come to public knowledge, anyway.

That journey begins in the second year of Duterte’s presidency, 2017. Magdalo, a military fraternity that has turned itself into a party-list organization, takes Duterte to the ICC for summary killings in his war on drugs. By then, the number of dead in the war, by the President’s office’s own admission, made yet in a self-published report, has reached 20,000.

Duterte tries to avoid falling under the jurisdiction of the ICC — being arrested and detained on its orders and being tried by it — by pulling the Philippines out of the treaty that justifies it. But the ICC says the process against him has already begun before the pullout and shall therefore proceed.

Sought for a ruling, the Philippine Supreme Court declares that the government is obligated to cooperate with the ICC. Duterte refuses to acknowledge the obligation.

And so does his successor, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., even after a falling-out with him. But Marcos says that if the Interpol comes with an ICC warrant he will be forced to comply and deliver Duterte to The Hague, on the grounds that the Philippines remains committed to the Interpol, if not to the ICC.

All that background is presented here in its barest form for a quick illustration, but it certainly could have been fleshed out in a further effort to make the waiting worthwhile somehow for the news audiences kept in the dark too long about what was happening.

Two side stories would have been particularly worth retelling: the one about the two confessed assassins for Duterte, Arturo Lascañas and Edgar Matobato, who themselves have managed to escape to The Hague to testify, and the other about former senator Leila de Lima, who, denied bail at every turn, had to spend nearly seven years in solitary detention on concocted charges related to drugs; that she fought and won her case under those conditions is itself a relevant commentary on Duterte’s own case.

Reasonably fair interpretation, by journalists themselves, could also have been added, this one for instance: Once delivered to The Hague, Duterte came under the exclusive jurisdiction of the ICC and it would become impracticable to get him out of it.

Brought out early enough, all of that readily accessible information would have set the right news tone for the day, stirred up an intelligent discourse, and helped keep the air at least sufferable.

And Duterte’s case being as much a judicial as a political one, therefore not going away soon, especially with his cultish cronies and followers, the long road to The Hague only bears repeating. – Rappler.com

6 hours ago

1

6 hours ago

1

![[DECODED] YouTubers posting lies, propaganda on Duterte-ICC issue can earn up to P20,000 daily](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2025/03/decoded-youtubers.jpg)