Upgrade to High-Speed Internet for only ₱1499/month!

Enjoy up to 100 Mbps fiber broadband, perfect for browsing, streaming, and gaming.

Visit Suniway.ph to learn

CEBU, Philippines – In Pangan-an Island, a member of the Olango Island Group in Cebu, one can find a graveyard of around 500 dead solar panels.

These abandoned solar panels belonged to the once-operating Pangan-an Solar Power Plant, a forgotten energy project of the Kingdom of Belgium and the Philippine government.

On December 7, 1998, the local government of Lapu-Lapu City (which has jurisdiction over Pangan-an), representatives of the Belgium embassy, and the Department of Energy led the switch-on ceremony of the Pangan-an Solar Electrification Project.

The Philippine and Belgian governments agreed to cooperate on the solar electrification project on Pangan-an Island on May 22, 1996.

PROJECT. The original board used for the switch-on ceremony of the Pangan-an Solar Electrification Project in 1998. Photo by John Sitchon/Rappler

PROJECT. The original board used for the switch-on ceremony of the Pangan-an Solar Electrification Project in 1998. Photo by John Sitchon/RapplerThe Olango Island Group consists of the main Olango island and seven satellite islets, namely Caubian, Camungi, Caohagan, Gilutongan, Nalusuan, Pangan-an, and Sulpa.

Camungi island is the closest to the mainland of Olango and is only separated by a waterway. The second nearest island to the mainland with a sizable population of at least 2,500 residents is Pangan-an, based on a 2020 census — Olango has a total population of at least 41,000 residents.

It takes at least 20 minutes to get to Pangan-an by boat. The travel path on the way to the islet from the mainland is surrounded by mangroves — a protected area covered by the Olango island Wildlife Sanctuary — making it difficult for locals to connect the island to the mainland’s power grid.

With an initial investment of P22 billion and the practicable travel distance considered, the solar electrification project was initiated to help address the Pangan-an community’s struggle for energy caused by the islet’s topography.

Based on the Department of Energy’s Department Order No. 98-07-002, dated July 30, 1998, the project was considered as “a test and showcase” for further policymaking in the field of solar power electrification.

However, after 15 years of operations, the entire power system shut down.

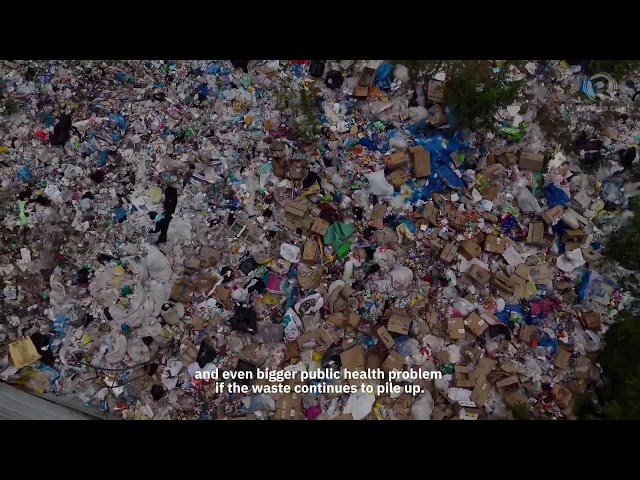

PLANT. A drone shot of the Pangan-an Solar Power Plant shows that there used to be around 500 working solar panels. Photo by Jacqueline Hernandez/Rappler

PLANT. A drone shot of the Pangan-an Solar Power Plant shows that there used to be around 500 working solar panels. Photo by Jacqueline Hernandez/RapplerDefunct

The solar power plant would be managed by the Pangan-an Island Cooperative for Community Development (PICCD), which empowered locals to become involved in the island’s energy production and distribution.

Marcos Estoy was a former PICCD staff before the solar plant ceased operations in 2013.

According to him, the lifespan of the plant’s batteries was estimated to last for only 10 years. Despite this, they were able to operate the plant for an additional five years.

“Giplanohan unta namo nga irepair unya mas dako man ang gasto sa repair sa battery (We supposedly planned to repair it, but the costs for the battery repairs were huge),” Estoy told Rappler.

The former PICCD staff shared that they did not have enough funds to cover the repairs that ranged between P8 million to P10 million. He added that their funds were only less than a million pesos.

Disasters like Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) in 2013 and Typhoon Odette (Rai) in 2021 also made it harder for Pangan-an to recover from economic losses. Hence, plans to pursue repairs were delayed indefinitely, Estoy recalled.

To conduct the repairs, he explained, the electronic devices needed to be transported to the mainland, which could add to the already expensive repair cost.

On top of that, bidding must be conducted with the private sector to see if there were any companies interested in shouldering the repair expenses, which would take time and more financial burden for the already struggling community.

RUSTED. Marcos Estoy, former staff of the Pangan-an Island Cooperative for Community Development, takes a closer look at the solar panels, which have rusted and deteriorated. Photo by Jacqueline Hernandez/Rappler

RUSTED. Marcos Estoy, former staff of the Pangan-an Island Cooperative for Community Development, takes a closer look at the solar panels, which have rusted and deteriorated. Photo by Jacqueline Hernandez/RapplerRappler went to the island and noted that it took 30 minutes to travel by sea from the Angasil Port in Mactan Island to the Santa Rosa Port in Olango Island.

“Wala na gyud siya nabalik og function (It never functioned again),” Estoy said.

Coping with demand

Without the solar plant, locals instead rely on gas-powered generator sets, which are known for emitting noise pollution and carbon monoxide that could be harmful at excessive levels.

Only a handful of families have generators in Pangan-an.

Maria Niña Aying, principal of Pangan-an Elementary School, told Rappler that the school used to rely on generators before it was energized with the help of solar panels.

She shared that the noise and smell from their school’s generator would often affect the health of their students and make classes challenging for teachers.

Since 2021, the local government and some nonprofit organizations have given solar power equipment and technology to areas in Olango, including Pangan-an.

Sabina Caballa, a barangay councilor of Pangan-an, told Rappler that they have received solar-powered street lights from the Lapu-Lapu City government.

“The light is important, especially since we have children who need it to study at night,” Caballa said in Cebuano.

Due to limited supply, some locals have no choice but to pay for gas-powered electricity which would cost them around P1,000 to P1,200 per month. In addition, the electricity provided would run from 6 am until 11 pm only.

Estoy told Rappler that the power rates are very expensive and only a few households are willing to pay that much. A large number of residents in Olango are fisherfolk who travel to the mainland to sell their fish.

“Naa pa gani mugamit og lamparilya (There are even those who still use oil lamps),” Caballa said.

Caballa added that the families who could afford solar power panels would often help out their neighbors who are unable to shoulder the costs of energy.

Rappler checked selling rates for 550-watt solar panels on Facebook Marketplace and found that they were being priced between P3,900 to P15,000.

According to renewable energy advocacy group Sustainable Energy and Enterprise Development for Communities (SEED4COM), the price of 550-watt solar panels in 2024 can be around P8,000.

Electrifying schools

Despite their current circumstance, the island’s public educational institutions remain as beacons of hope for the families of Pangan-an.

Pangan-an Elementary School and Pangan-an High School are powered by an off-grid solar system that allows the teachers and students to utilize electronic devices 24/7.

In 2024, the Pangan-an Elementary School received solar panels from private companies like Merck Incorporated and Aboitiz Foundation.

Prior to this, Aying said, the school frequently experienced power outages, which rendered fans and other electronics almost unusable during class hours. The principal recalled how some students and teachers would complain about the heat inside their classrooms during warmer seasons.

POWERED. The elementary and high schools of Pangan-an received a 10 KVA solar panel from the Aboitiz Foundation. Photo by Jacqueline Hernandez/Rappler

POWERED. The elementary and high schools of Pangan-an received a 10 KVA solar panel from the Aboitiz Foundation. Photo by Jacqueline Hernandez/Rappler“Makagamit na og gadgets, makaprint na, which is comfortable na ang mga bata mao na karon if you can see in our classroom, maka-TV na jud mi, dili na mi mapagngan,” the principal said.

(We could use gadgets now, print, which is comfortable for the kids, and now, if you can see in our classroom, we can use the TV, it won’t turn off on us.)

Aying added that the school does not have to pay a single centavo for electricity. However, the principal acknowledged that they would still have to shell out money for maintenance costs every three to five years for the solar panels and batteries.

“If you will just use it wisely and use it the right way, you can use the solar for around 24 hours. And I’m very happy for that, that there are stakeholders who helped us for this,” the principal said in a mix of English and Cebuano.

ENERGY. With the off-grid solar system, the students of Pangan-an Island enjoy classes with dance and music videos. Photo by Jacqueline Hernandez/Rappler

ENERGY. With the off-grid solar system, the students of Pangan-an Island enjoy classes with dance and music videos. Photo by Jacqueline Hernandez/Rappler– Rappler.com

Reporting for this story was supported by the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities under the Jaime Espina Klima Correspondents Fellowship.

3 months ago

17

3 months ago

17