Upgrade to High-Speed Internet for only ₱1499/month!

Enjoy up to 100 Mbps fiber broadband, perfect for browsing, streaming, and gaming.

Visit Suniway.ph to learn

MANILA, Philippines — Why do some roads in Metro Manila become death traps during floods while others remain passable? According to a disaster scientist, some roads were actually built over waterways.

Mahar Lagmay, executive director for Project NOAH, pointed out that when heavy rains hit — whether by the southwest monsoon or a tropical cyclone — water flows following its original path.

“Ang totoong dahilan kung bakit binabaha ang mga kalye na nakikita natin ngayon sa social media. Daanan talaga siya ng tubig pero nilapatan natin ng kalye,” he said in a Facebook post on Monday, July 21.

(The real reason streets are flooding as we’re seeing now on social media is because these areas are natural waterways that we’ve paved over with roads.)

Flooding has hit several parts of Luzon, including Metro Manila, as low pressure areas and the habagat continue to bring heavy to torrential rain in populated, urban and low-lying areas.

It’s all over social media. Residents, field reporters and government officials have captured waist-to-chest-deep floodwaters across the country.

Floodwaters that swelled too high left vehicles stranded for hours along the North Luzon Expressway (NLEX) on Monday night.

In Manila, commuters waded through floodwaters along Taft Avenue and España Boulevard, where the water rose to gutter level.

Every Filipino recognizes the scene of flooded streets, stranded vehicles and waterlogged communities. It happens without fail whenever heavy rains hit. So why hasn’t this decades-old crisis been solved?

It's a matter of design, too

A 2017 study by the University of the Philippines (UP) identified key flood causes: more concrete surfaces, denser buildings, clogged waterways, garbage-filled drains and development on plains where water used to flow naturally.

The geography seemingly makes flooding inevitable as Metro Manila sits on a massive floodplain where four rivers, Marikina, Pasig, San Juan and Tullahan, serve as water channels for the Marikina River Basin.

Analyzing 23 flood-prone streets identified by the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA), researchers found that these roads were built at the same level as nearby creeks and low-lying roadsides, instead of being elevated to reduce the risk of flooding.

“Many flood-prone areas are where streets and creeks intersect; others are areas where water accumulates,” the study said.

How high above are roads built. Ricardo Papa Street along Rizal Avenue in Manila was among the cases cited, with researchers discovering that it is “lower than the roadside and lies below the tops of three stream segments.”

In Quezon City, the Philcoa area sits only 3.8 meters above the nearby creek, according to the study. R. Papa in Manila is even lower, at just 1.38 meters above the creek bed.

Meanwhile, the road along C-5 Bagong Ilog in Pasig City stands just 3.92 meters above the stream bed.

Lack of drainage networks. Researchers also found that in eight sites, drainage networks seemed to be missing where waterways should have passed, possibly covered over by concrete.

In UP Diliman, researchers observed a larger channel along C.P. Garcia Avenue, which sits only 1.25 meters above the banks. It is crossed by 1-meter diameter culverts, which serve as tunnels for streams or drainage under the road.

“While it is built up above the lowest portion of the channel, it is still below the main channel banks and remains susceptible to flooding,” the study added.

Compared to Don A. Roces Avenue in UP Diliman, which the study said is “sufficiently elevated” at 4 meters above the creek bottom, C.P. Garcia is more vulnerable to flooding and quickly becomes impassable during brief but intense thunderstorms.

“These show that the construction of roads relative to the elevation of intersecting creeks affects whether or not the roads get flooded,” it added.

Elevate roads above creeks

The UP study further explained that flood-control projects typically follow technical standards based on how often floods are expected to occur. These are determined by the size of the area that collects rainwater.

If runoff data or records of the year’s biggest floods are unavailable, the study said that engineers rely on rainfall data to estimate the likelihood of flooding.

Researchers said flooding in low-lying roads could be addressed by adopting the design of A. Roces Avenue in UP Diliman, which features a hydraulic structure beneath the road capable of handling large volumes of water during heavy rains.

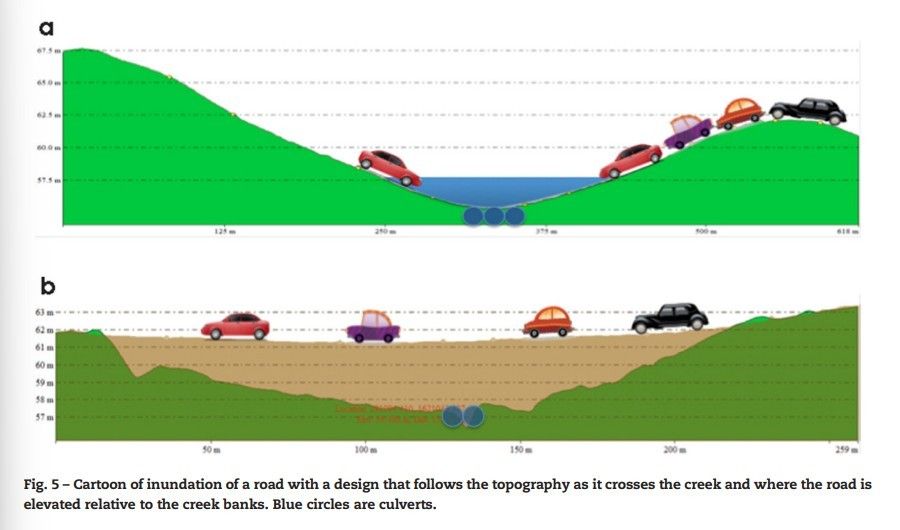

Two illustrations compare a road built following the land’s natural slope across a creek, and another road elevated above the banks, with blue circles marking the culverts that allow water to pass through.

Alfredo Mahar Lagmay via Facebook

It recommends placing steel mesh drains along streets to help manage rainwater runoff that tends to pool rapidly in low-lying areas. According to the researchers, it would be best if the underground storage for excess rainwater is designed to drain into the creek.

“Roads that follow topographic lows, even if they are above the creek's bank, should have enough clearance or freeboard to accommodate creek swelling,” the study said.

“Roads above creeks, therefore, must be designed and constructed in the same manner as roads that cross large rivers,” it added.

Researchers stressed that beyond easing floods, this solution could help motorists save from increased fuel consumption and curb potential income losses from traffic gridlocks.

As Tropical Depression Dante becomes the fourth storm to hit the Philippines this year — on top of climate change exacerbating effects — the pressure mounts for the government to deliver real flood solutions.

Years of multi-billion peso flood budgets have been approved with seemingly little to no impact. With P248.1 billion earmarked for 2025, Filipinos are watching.

12 hours ago

2

12 hours ago

2