Upgrade to High-Speed Internet for only ₱1499/month!

Enjoy up to 100 Mbps fiber broadband, perfect for browsing, streaming, and gaming.

Visit Suniway.ph to learn

Ahead of a campaign sortie in Laguna on March 22, the press conference of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s senatorial slate opened with a question from local media — if elected, what can Alyansa para sa Bagong Pilipinas do to address the deteriorating agricultural industry in the province?

“Almost all the land that used to yield thousands of sacks of rice has been turned into subdivisions, buildings, and houses,” the journalist quipped.

The administration-allied candidates were quick to respond with the promise to support the land use bill, a key piece of legislation that has been languishing in Congress for decades.

Passing the said measure, however, will take a higher level of political will — specifically, standing up to the Villars, who have been a crucial factor in the bill getting stuck in the legislative mill in the last decade.

Can the administration-allied candidates do that, when they are in an alliance with a scion from the Villar dynasty?

ADMINISTRATION SLATE. President Ferdinand Marcos and his 2025 senatorial candidates. Photo from Alyansa para sa Bagong Pilipinas

ADMINISTRATION SLATE. President Ferdinand Marcos and his 2025 senatorial candidates. Photo from Alyansa para sa Bagong PilipinasCost of urbanization in Calabarzon

This was not the first time the Alyansa candidates faced the question on the rapid conversion of farmlands. Just the day before, during their visit to Cavite province, the aspirants were left no choice but to address the issue after local media brought it up.

“With the urban sprawl happening now, that’s really unavoidable,” Tolentino said. “Balancing this is part of Cavite’s urban planning and zoning plans. I can’t speak for the provincial government, but it’s not like there’s nothing left.”

Hard data, however, back the noted significant reduction of agricultural lands in Calabarzon, the vote-rich region that the administration slate courted when it barnstormed two of its provinces the past weekend.

In 2002, Calabarzon’s total agricultural land was at 588,500 hectares, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority. By 2021, the number had been reduced to 110,538 hectares, based on a report by news outlet OpinYon, citing the Department of Agriculture.

Production areas for agriculture was “declining at an annual average rate of 0.15% in the province” as of 2015, according to the Calabarzon Regional Development Plan for 2023 to 2028.

“From 1988 to 2018, the Department of Agrarian Reform approved around 21,072 hectares of agricultural land for conversion. However, in some instances, premature conversion happens, especially when the LGU reclassifies agricultural lands for other uses through its [local council] without going through the proper process or when agricultural lands are abandoned and left idle,” the report read.

“The growing population has driven the increased demand for settlement, industrial, and commercial lands. Moreover, conversion intensified as the land value increased. Increasing agricultural land conversion without proper land evaluation could threaten food security and increase the farmers’ vulnerability to displacement,” it added.

Decades-long battle in the legislature

A national land use code, first introduced in Congress during the presidency of Corazon Aquino, would have mitigated the diminishing number of agricultural lands.

Local government units (LGUs) have their own comprehensive land use plans, but without a national framework, the CLUPs tend to vary per city or municipality. Some mayors prioritize short-term economic gains, at the expense of sustainable development.

The Marcos administration has included a national land use measure in his priority measures. In fact, a bill on the subject already hurdled the House of Representatives two years ago.

That bill harmonizes existing but conflicting laws on land use, sets strict parameters on what prime agricultural lands can be converted for non-agricultural purposes, and prevents LGUs from reclassifying protected agricultural lands. (Left-leaning bloc Makabayan, however, opposed the current version of the bill, arguing it is anti-poor for supposedly allowing the conversion of farmlands for profit-making ventures.)

Despite its classification as a priority measure, the bill is unlikely to pass in the 19th Congress, as the approved House bill and its Senate counterparts remain in limbo in the upper chamber — specifically, in the committee of Senator Cynthia Villar.

Where national land use bills are left to die

Villar has presided over the Senate environment committee since 2016. Since then, national land use bills referred to her committee have met a slow but sure death.

As chairperson of the panel, she has the prerogative to set its agenda, and determine which measures to take up.

Graphics by Nico Villarete/Rappler

Graphics by Nico Villarete/RapplerThe Villars have been lukewarm toward — if not outright against — the bill. When the House under the current Congress passed the land use bill in May 2023, Deputy Speaker Camille Villar did not cast a vote, even though she was recorded to be present in the plenary. The last time someone from the family supported the proposal was when then-congressman Mark Villar voted yes to the bill in 2013.

The family matriarch herself has a history of not caving in to pressure from the powers-that-be in Malacañang on the subject.

In 2019, when then-president Rodrigo Duterte requested that Congress pass the national land use bill within a year, Villar said she was opposed to the idea of a centralized body on land use.

“Who will remove it from the local governments to centralize it? Do you want all the ire of the mayors in the Philippines? That’s their power,” she had said.

The Villar family’s involvement in politics and real estate has long sparked criticisms of potential conflict of interest. The patriarch, former Senate president Mark Villar, built his fortunes to become the country’s wealthiest man through his real estate empire.

The family owns leading homebuilder Vista Land, which has been involved in the conversion of farmlands into subdivisions in the provinces.

In Cavite and Laguna, where local media found the need to raise the issue of farmland conversion, the company has huge footprints. A report by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism describes Vista Land as the biggest property developer in Imus. In Calamba, its subsidiary Camella Homes boasts a 14-hectare gated subdivision.

In 2022, Senator Villar clashed with her colleague Raffy Tulfo over the issue. She insisted that her family business purchases agricultural lands only in urban areas and not in the provinces, and maintained that subdivisions are necessary so that people will have a place to live.

“It’s not the amount of farmlands. It’s the efficiency of using these farmlands,” Villar had said, as quoted by GMA News. “Even with smaller area of farmland, you can do better and earn more.”

Beyond empty promises

Senator Cynthia is term-limited for the 2025 polls, and she is hoping to pass the baton to her daughter. Deputy Speaker Villar was absent from the Calabarzon rallies, when the question on farmland conversion was raised. (We messaged her staff about her stand on the land use bill, and asked why she did not cast a vote on its passage in 2023, but we have yet to receive a reply.)

Her inclusion in the Alyansa slate, however, dilutes her co-coalition members’ pro-land use stance. Passing the measure means not just speaking favorably about it, but perhaps backing a change in leadership in the Senate environment committee, one who does not carry the Villar surname.

“Candidates will say anything to get votes, these pronouncements are merely lip service. The national and use bill will never be passed so long as political dynasties like the Villars have vested interests in land rights,” Joana Castro, spokesperson for environmental group Kalikasan, told Rappler.

“In order for these bills to be passed, we must first end political dynasties and ensure that the interests of farmers, indigenous peoples are genuinely represented in congress and their voices and insights truly valued and not just used for lip service,” she added.

We asked Alyansa candidates present during the March 22 press conference in Laguna: how can you ensure that your pronouncements are not empty promises?

Alyansa campaign manager, Navotas Representative Toby Tiangco, tried to sidestep the question, saying the candidates can’t provide an answer, because whoever gets elected as environment committee chairperson would depend on the composition of the new Senate.

Other senatorial aspirants, however, chose to answer.

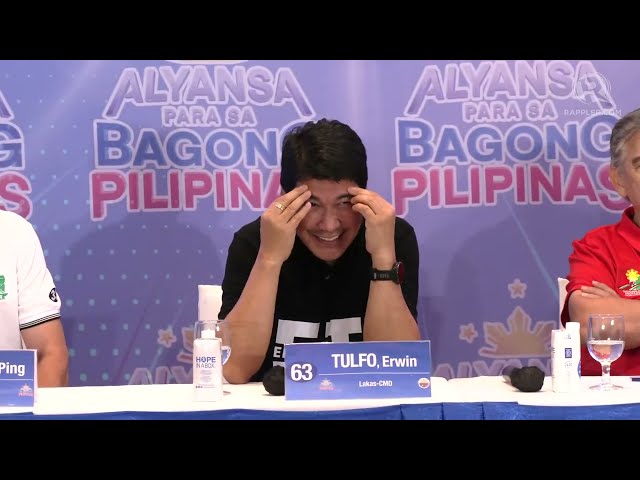

“One solution is that I will move to elect Erwin Tulfo as new chairman of the committee on environment,” former senator Panfilo Lacson joked.

Congressman Tulfo chuckled before referencing Senator Raffy’s public argument with Senator Villar: “You know my brother got into trouble because of that before.”

“We have to solve this problem. Otherwise, it will go on and on. We must pass the National Land Use Act. [The system] has been abused,” Tulfo said. “Some people will get hurt, but we can’t do anything. We have to be for the people, not for the few. If we keep on closing our eyes, especially in the Senate, nothing will happen.”

“This is on record, you’ve heard what we said, I am for the land use plan,” former interior secretary Benhur Abalos added.

Those are categorical, determined pronouncements, but the Alyansa candidates’ sincerity will be evaluated not through words, but tangible results. – Rappler.com

1 month ago

13

1 month ago

13

![[Pope Watch] A campaign against Cardinal Tagle?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2025/04/pope-francis-funeral-saint-peters-basilica-april-23-2025-022-scaled.jpg)