Upgrade to High-Speed Internet for only ₱1499/month!

Enjoy up to 100 Mbps fiber broadband, perfect for browsing, streaming, and gaming.

Visit Suniway.ph to learn

MANILA, Philippines — Almost every Araling Panlipunan teacher in Masinloc, Zambales knows the question is coming.

Here in the closest Philippine town to Scarborough Shoal — home to fishing families who pray for calm seas with no Chinese vessels prowling nearby — students often wonder why the Philippines' 2016 arbitral victory has not kept China's maritime harassment at bay.

"Even we teachers ask this question," Ronnel Mas, a Grade 9 Araling Panlipunan teacher at Taltal National High School, recounts to Philstar.com. "Despite the decision, why is China still not complying?"

In 2016, the Philippines won its biggest legal victory against Beijing when an international tribunal rejected its sweeping claims in the South China Sea. But nine years on, teachers in this coastal town have found themselves educating a generation of students who continue to watch their families or distant neighbors lose at sea despite international law being on their side.

Over the years, the teachers say several of their students' parents have abandoned fishing entirely and turned to farming or other work to survive. But for those who still head out to the contested waters, the economic toll has been steep — and it's leading to empty seats in the classroom.

Paolo Echon, who teaches Grade 8 Araling Panlipunan at Santo Rosario Integrated School, says one of his students – often absent from class – has seen his family's income plummet due to China's harassment. “They used to earn around P15,000 a month when there were no tensions near Bajo de Masinloc (Scarborough Shoal),” Echon told Philstar.com. “Now it’s just 1,000.”

The father of Echon's student is among several residents of Masinloc who have had to fish farther and farther out at sea due to the constant presence of Chinese vessels, leading to extended trips that drive up the cost of fuel.

Four teachers from Masinloc, Zambales who spoke to Philstar.com say this situation has bred frustration and resentment among their students. There are questions about why the Philippines doesn't simply "fight back."

But as students vent about being “bullied" by China, their Araling Panlipunan teachers say it is the perfect opportunity to teach them the value of restraint and the rule of law.

De-escalating anger

Students' emotions about the presence of Chinese vessels in the West Philippine Sea run high in Bryan Estigoy's classroom. For the Grade 10 Araling Panlipunan teacher, lessons on the Philippines' territorial dispute with China inevitably become personal.

"One of my students’ parents was among those harassed by Chinese vessels — the same scenes we see in videos and watch on the news," Estigoy tells Philstar.com in mixed English and Filipino. "They would ask, 'Don’t our parents have rights to fish there, too?'"

Even as he calls them "victims of circumstance," Estigoy refuses to let the lesson be all about their frustration. Instead, the teacher says he guides them toward studying the legal foundations that underpin the Philippines’ maritime claims.

"As students, what power do we really have? How can someone your age fight for our rights?” Estigoy recalls asking his class. "I ask them to limit their answers so that they are grounded in facts and legal basis."

“I feel their anger,” the teacher says. “But the reason we go to school is to gain deeper knowledge of the issue. There’s already been a ruling, and we won. We must stand for what’s right — especially what the UNCLOS and our own Constitution says. The students need to know that.”

Echon, meanwhile, recalls having to field tough questions from his students, who were rattled after the actions of Chinese vessels' near Bajo de Masinloc in December 2024. China Coast Guard and military vessels fired water cannons at Philippine vessels conducting patrols to support Filipino fishermen in the area — most of whom his students knew personally as relatives or neighbors.

“One student asked, ‘Sir, didn’t we win in the international court? Then why are our parents still struggling to fish?’” Echon says. “When questions like that come up, it's not enough to just be sympathetic, but we lay down the legal basis behind the Philippine government's stance."

Similarly, Mas makes sure to walk his students through the lengthy 2016 arbitral ruling that invalidated China's so-called nine-dash line claim.

"I know it is an almost 500-page ruling, but it serves as a case digest for them," Mas says. "As an economics teacher, I ask them to draw concrete conclusions about how the ruling affects them socio-economically, because many of their parents are in the fishing industry."

At Santo Rosario Integrated School, Echon says that out of his 111 Grade 8 students, he knows three who come from fishing families affected by tensions near Bajo de Masinloc.

Meanwhile, at Bamban National High School, Estigoy estimates that around 50 of his 179 Grade 10 students, or nearly 30%, still have families dependent on fishing in the contested waters.

"You can really see that when fishers don't get to sail, some kids stop coming to school because their families can't make ends meet," Estigoy says.

Fighting disinformation

The economic hardship has caused anxiety that teachers say is being amplified by what students see online, with some jumping to conclusions that it's time for a tit-for-tat war.

"When we talk about the West Philippine Sea, the [students] often think we are heading to war or that something bad is about to happen," says Reggie Sison, who teaches values education at Bani National High School and focuses his lessons on the human rights aspect of the dispute. "That’s why it’s important we teach them what’s real, what’s legal, and what’s still ours.”

While students are well aware of China's persistent aggression against Filipino fishermen, Echon says he tries to teach his students to view the issue on a regional level to understand how the Philippines cannot simply declare war against Beijing.

"We can't always be antagonistic toward them, because there has to be a sense of understanding and belonging — a way for us to coexist on the same continent," Echon says. "We can’t let misinformation or misconduct lead to something like World War III."

Waiting for a standard map

When it comes to teaching materials, teachers say they have to research which maps to use — and it's not always clear which version aligns most with the 2016 arbitral ruling.

"I use the Mercator map sometimes," Bryan Estigoy says. "But I'm always looking [to] more updated maps to show the students."

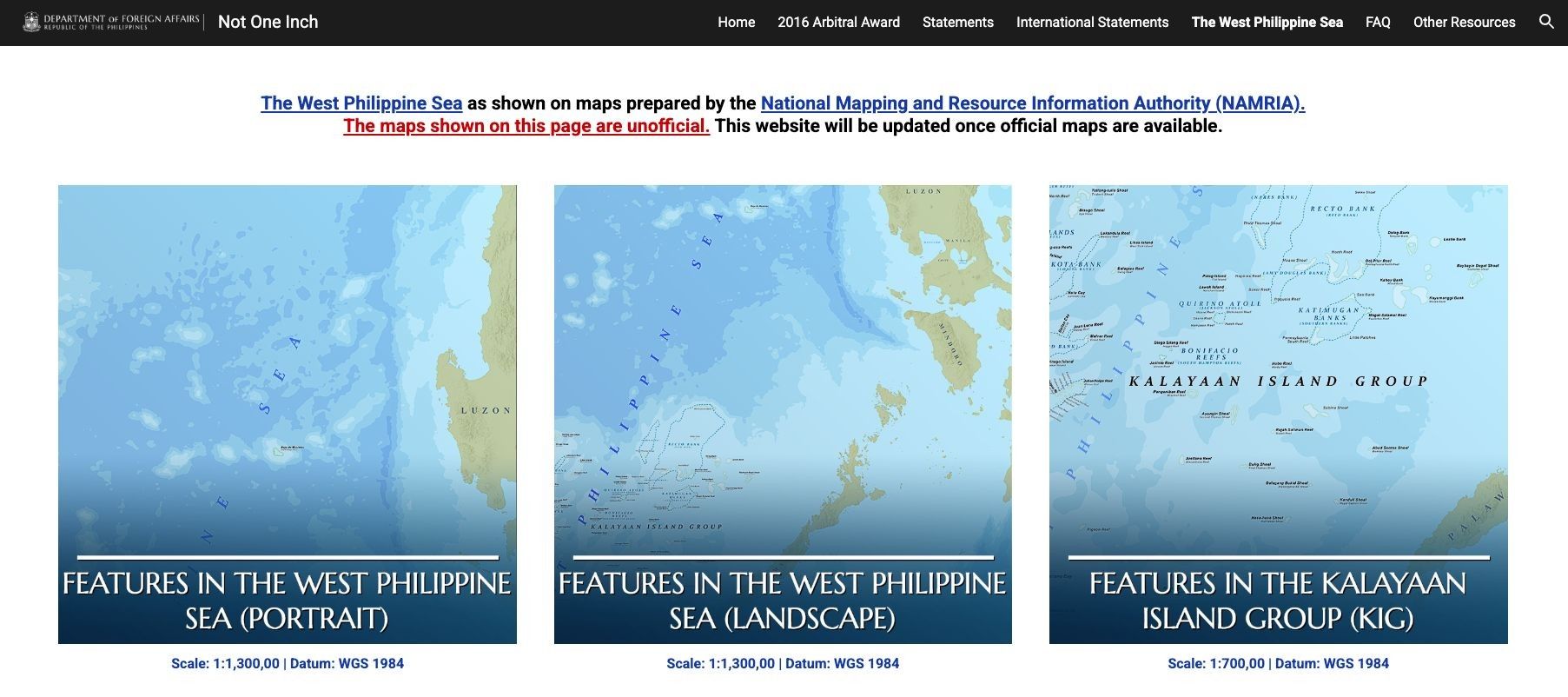

In November 2024, the Philippine Maritime Zones Act was signed into law, which defines the country’s internal, archipelagic, territorial, contiguous, and exclusive economic zones (EEZ) in line with international law and the 2016 arbitral ruling. Shortly after, the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA) said it would soon release an official map that reflects the country's maritime domain and entitlements under the law.

For now, teachers searching for reliable visual aids can turn to the unofficial NAMRIA maps displayed on the Department of Foreign Affairs’ microsite on the arbitral ruling.

But the teachers also believe that having a standardized, government-endorsed map would go a long way in clarifying the exact maritime boundaries that they will teach their students.

“If we have an official map, it will also show that we ourselves are asserting and standing by the arbitral ruling,” Mas says. “As long as the nine-dash line still appears on other maps, students will continue to be conditioned to believe that we have actually have no claim."

The map showing the Philippines' maritime features in the West Philippine Sea, as shown in the DFA's microsite, are not yet the official version, July 14, 2025.

Screengrab July 14, 2025; 1:57 a.m.

Creating advocates, smart voters

Drilling down lessons on the West Philippine Sea and other contemporary issues are the four teachers' way of raising socially conscious citizens, whichever field they decide to enter in the future.

“For me, I’ll know my teaching has succeeded if the knowledge didn’t just enter their minds — it was taken to heart and put into practice,” Estigoy says. “That’s where real learning happens.”

He hopes his students grow into citizens who not only understand territorial rights but also stay aware of what’s happening around them — and are willing to engage, whether through advocacy or informed conversations.

“For example, if I see a former student posting something like ‘Pilipinas, ipaglaban ang karapatan (fight for our rights),’ even something that simple already shows the impact of teaching grounded in legal principles,” he says. “It means they’re thinking critically.”

Part of that, Estigoy adds, is helping students think clearly about the kind of leadership and laws the country needs. “I’ll consider it a success if they grow into people who can choose leaders wisely — those who will truly defend our rights and pass laws that serve the country,” he says.

Teacher-subject mismatch

The path forward, according to Ariel Vicedo, Education Program Supervisor for Araling Panlipunan in Zambales, is to build up teachers' knowledge of the territorial dispute — because the quality of the materials they use in class largely depends on how well they themselves grasp it.

"You cannot teach what you don't have," Vicedo tells Philstar.com. "Teachers should be one step ahead of their learners when it comes to the West Philippine Sea so they can teach it properly."

As in other subject areas, a large chunk of Araling Panlipunan teachers in Zambales did not actually take up the specialization in college. Vicedo estimated only six in 10 Araling Panlipunan teachers in his division majored in the subject, meaning 40% are teaching outside their specialization.

"It's easy to find AP teachers," Vicedo explains. "But finding AP teachers who have the heart and love for Araling Panlipunan — that takes time. It takes time before you truly love what you're teaching, especially if you didn't major in it."

The four teachers who spoke to Philstar.com, Vicedo says, embody exactly what he looks for when observing classes in the schools under his supervision: educators who guide their students to understand their identity as Zambaleños who know their "personal histories."

"It's not just about the West Philippine Sea," Vicedo says. "For these children, history is already personal."

2 days ago

7

2 days ago

7