Upgrade to High-Speed Internet for only ₱1499/month!

Enjoy up to 100 Mbps fiber broadband, perfect for browsing, streaming, and gaming.

Visit Suniway.ph to learn

MANILA, Philippines — Should Vice President Sara Duterte face an impeachment trial, expect her bank records to be among the documents the House prosecution will request.

When Sara was impeached in February, the House accused her of amassing unexplained wealth, with over P2 billion reportedly coursed through joint accounts with her father, Rodrigo Duterte, at BPI and BDO between 2006 and 2015.

Under Article IV of the impeachment complaint, the House claimed she received at least P111.634 million during that time while holding public office in Davao City, which they said is “grossly disproportionate to her legitimate income.”

But just how can the prosecution get hold of those “confidential” records? Retired Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonio Carpio said there are two ways.

Bypassing bank secrecy via Impeachment

One legal avenue is through Republic Act 1405, or the Bank Secrecy Law. While it generally protects deposits as “absolutely confidential,” he said it makes exceptions, including in impeachment cases and when the depositor gives their written consent for their records to be examined.

In an interview with DZMM Teleradyo, Carpio explained that the House prosecution can invoke this law when they file a motion for a subpoena duces tecum to obtain deposit records made to Duterte’s account at the Bank of the Philippine Islands (BPI).

A subpoena duces tecum is a legal order compelling a person to appear before a court and produce the requested documents.

“Ngayon (Now), because this is an impeachment case, of course the prosecution will file a motion for subpoena duces tecum to subpoena the bank records of Sara in BPI,” Carpio said on Wednesday, July 2.

When the motion is filed. So what happens after the motion reaches the Senate impeachment court? It can also go one of two ways.

The Senate President, acting as presiding officer, can rule on it alone or bring it to a vote among the senator-judges.

If the presiding officer approves the motion but a senator-judge objects, the issue will be decided by the impeachment court as a body where only a majority vote is needed.

“[T]he presiding officer — the Senate president can, on his own, decide that (the motion) or can throw it to the body,” Carpio said.

“Now, if the presiding officer decides on his own, and a member does not agree, then that member can ask for a vote by the entire body,” he added.

Although senator-judges are free to vote against the motion, Carpio said that doing so, especially in a case involving the vice president’s bank records, may provoke public criticism, which the Senate will have to confront.

He drew parallels to the impeachment trial of former President Erap Estrada in 2001, when the Senate refused in a 11-10 vote to open a damning envelope believed to hold proof of his hidden wealth.

In protest, the prosecution walked out and the public was furious, eventually leading to the Second EDSA Revolution and Estrada’s resignation days later.

Ombudsman and AMLC

Aside from citing the impeachment as grounds for subpoenaing Sara’s bank records, Carpio said a second legal avenue is obtaining the depositor’s written consent, which is already provided under laws governing an official’s submission of Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth (SALN).

By law, through the Republic Act 6713, public officials must file their SALNs every year, listing not just their assets and liabilities, but also business interests and financial ties. The Constitution requires that these be open to the public to promote transparency.

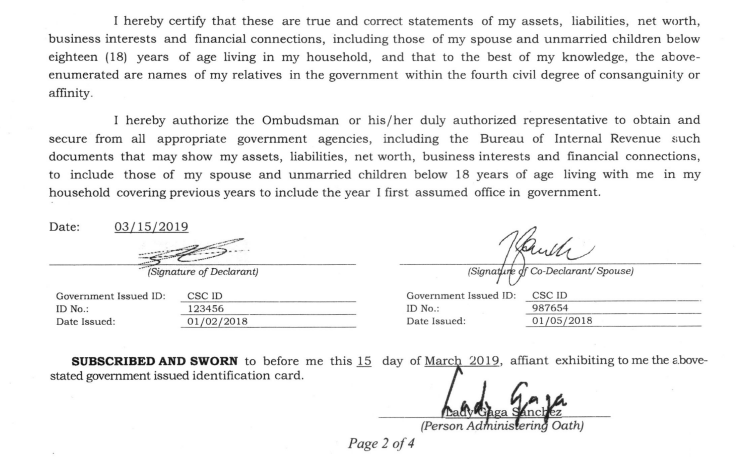

According to Carpio, the SALN form includes a provision tantamount to a waiver, granting the Ombudsman or their authorized representative the authority to verify the disclosures through any appropriate government agency.

“So the Ombudsman has the power to ask the Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) to send the records of public officials with respect to their bank accounts, dahil may reporting ‘yung banks to AMLA (Anti-Money Laundering Act) ‘pag it’s over half a million pesos,” he added.

A sample sworn statement of assets, liabilities and net worth, containing the certification and authorization that public officials and employees have to sign.

Civil Service Commission

Carpio recalled how, during former Chief Justice Renato Corona’s impeachment trial, the Ombudsman managed to secure his bank records from the AMLC and present them in court when subpoenaed.

“So very few people know this, but every public official, when you file your SALN, you give a written authority,” he said.

He explained that this provision qualifies as the first exception under the Bank Secrecy Law, which permits disclosure with the depositor’s written consent.

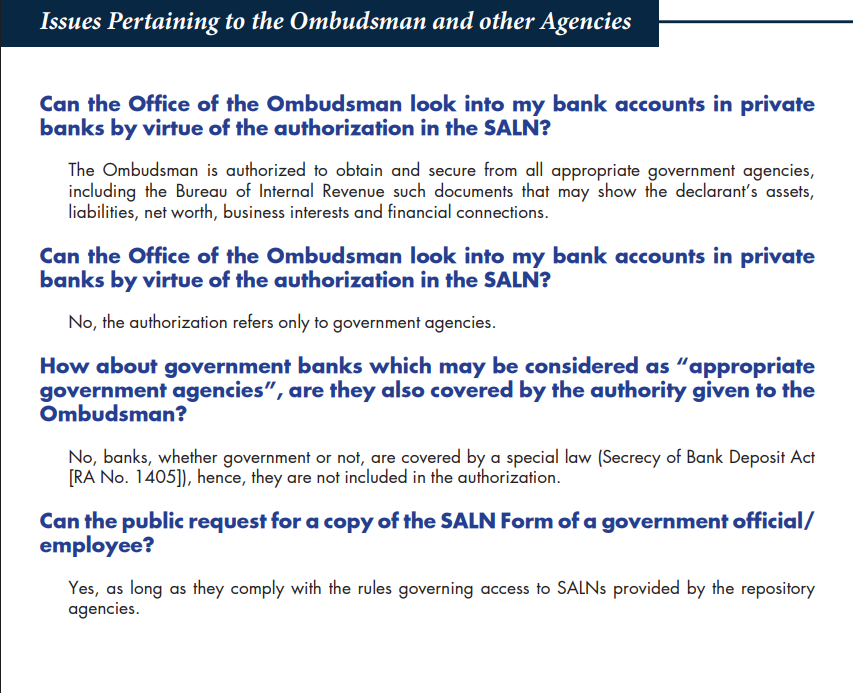

Still, the SALN alone does not give the Ombudsman direct authority to examine a public official’s bank accounts. Access can only be granted through the AMLC, which is a government agency mandated to investigate financial transactions and records.

The Civil Service Commission's explanation to the frequently asked questions on the authorization granted to the Ombudsamn through the SALN.

Civil Service Commission

“So pwede rin mag-request ‘yung ombudsman [sa] Anti-Money Laundering Council, pero hindi pwede sa bangko … because the Anti-Money Laundering Council is a government agency that’s created by law,” Carpio said.

(“So the Ombudsman can also request from the Anti-Money Laundering Council, but not directly from the bank … because the Anti-Money Laundering Council is a government agency created by law.)

Besides filing a motion to subpoena the bank deposits, Carpio said that the prosecution could also ask the impeachment court to subpoena the Ombudsman, who may have the bank records.

According to the articles of impeachment, Sara’s SALNs from 2007 to 2012 and 2016 to 2017 show her net worth jumping from P13.88 million to P44.83 million — far more than what she could’ve earned as vice mayor and mayor.

What Sara argued. Sara, in her answer ad cautelam, brushed off the allegations as “hearsay,” saying the House relied on documents shown in a 2016 article involving documents provided by former Sen. Antonio Trillanes.

But according to Vera Files, the Ombudsman actually confirmed the AMLC had a set of bank records that looked similar to what Trillanes had — records that a source told the publication were accurate.

With the 20th Congress about to convene, questions on whether the trial would proceed will finally be answered. The Senate, however, has maintained that it would likely put Sara's motion to dismiss the impeachment altogether to a vote.

3 days ago

6

3 days ago

6