Upgrade to High-Speed Internet for only ₱1499/month!

Enjoy up to 100 Mbps fiber broadband, perfect for browsing, streaming, and gaming.

Visit Suniway.ph to learn

MANILA, Philippines – At the heart of the Supreme Court (SC) oral arguments on the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) fund transfer are two edicts — a provision and a circular — but why were these issued in the first place?

Lawmakers inserted a special provision in the 2024 General Appropriations Act (GAA), which allows the government to start tapping into the “fund balance” of government-owned or -controlled corporations (GOCCs) to finance its unprogrammed appropriations.

It was then the Department of Finance (DOF) issued marching orders — in PhilHealth’s case, a circular dated April 24, 2024 on the transfer of P89 billion back to the national treasury.

The state insurer had completed three of its four scheduled transfers to the National Treasury before the Supreme Court issued a temporary restraining order. By then, P60 billion had already been remitted to the government.

The transfer has resulted in uproar from the healthcare community, advocates, and the public — with many arguing that PhilHealth funds should only be used for the healthcare of the Filipino people. The Supreme Court is tackling three petitions separately filed by groups led by Senator Aquilino “Koko” Pimentel III, retired Supreme Court senior associate Justice Antonio Carpio, and former lawmaker Neri Colmenares.

During the Supreme Court oral arguments, Solicitor General Menardo Guevarra said that the government was merely using its “common sense” in sourcing funds for other key projects.

But discussions at the High Court so far suggest there’s probably more to this.

The issue of unprogrammed appropriations

The PhilHealth fund transfer opened discussions on the government’s ballooning allocation for unprogrammed appropriations (UA) or standby funds.

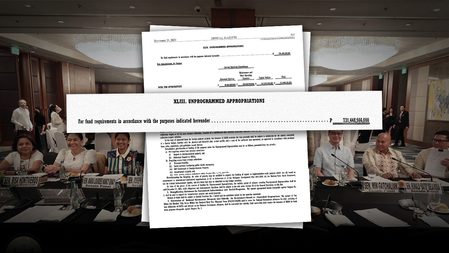

It’s an issue opposition lawmakers have also brought before the Supreme Court — in 2024, unprogrammed funds soared to P731.45 billion in the 2024 General Appropriations Act (GAA) from the P281.91 billion requested by the National Expenditure Program.

Colmenares, counsel for petitioners, pointed out that the changes were made at the bicameral committee level, which is a red flag as budget proposals should go through the House of Representatives first. These changes were made at the finishing stages — “It’s as if the [bicameral committee] said, ‘Well… House, Senate… we know more than you. We can include here certain items you haven’t thought about.’”

“In fact, the [committee is] even telling the president as if that, ‘Look, Mr. President. There are P449 billion worth of projects that you haven’t even considered, Mr. President. We are the ones to do it,’” said Colmenares.

Unprogrammed appropriations are considered the government’s standby funds or something it can dip into when financing of certain projects are not explicitly provided for in the national budget or the GAA.

Why tap PhilHealth?

Petitioners have pointed out that the transfer is unconstitutional because, in the first place, the Universal Health Care (UHC) law provides that the state insurer’s excess funds should be limited to healthcare only.

Under Section 11 of the law, reserve funds should have been used to improve benefit packages, lower contributions of paying members, and use it for investments. Supreme Court Associate Justice Amy Lazaro-Javier noted that these should be “sacred” and “untouchable.”

The Office of the Solicitor General provided a list of projects that will be funded by unprogrammed appropriations. Among these are “routine maintenance of national roads” and the financing of right-of-way acquisitions — projects that are far from being connected to healthcare services.

Some of the projects listed under unprogrammed appropriations have also secured foreign funding, prompting Javier to ask: “Is there an urgency to transfer the PhilHealth funds when the project is already fully-funded?”

Guevarra only said that this would require “delving into the wisdom of the legislature.”

“If a project that has already been identified and sufficiently funded is considered to be non-implementable for the given fiscal year, then I think it is the decision of Congress… to move it to the unprogrammed appropriations in the meantime,” he said on the second day of oral arguments on February 25.

To which, Javier replied: “So we have unused funds for the project and yet we still got money from PhilHealth to supplement this fund that has been unused for years?”

For pork barrel?

Zy-za Nadine Suzara, a public budget analyst invited by the High Court as one of the amici curiae (friends of the court) or experts, noted that this is a “new scheme for massively funding pork barrel.”

“Congress severely distorted the budget by defunding strategic development programs and projects that were part of the original proposal in the programmed appropriations,” she said during the first day of oral arguments on February 4.

Some key transport projects have been placed under unprogrammed appropriations, including the Light Rail Transit Line 1 Cavite Extension, the Metro Manila Subway Project, and the North-South Commuter Railway System.

This means that the projects have since lost their funding and will now rely on the government’s extra funds for completion, which may take longer than planned.

“What happened to the freed up fiscal space when the strategic and priority infrastructure projects were transferred to the unprogrammed appropriations? The 2024 GAA shows that an avalanche of funding went to departments where the hard and soft projects of legislators are traditionally lodged,” Suzara said.

Suzara also noted that from 2022 to 2024, 20% of the government’s national budget was allocated to pork barrel.

What the government says

Guevarra said the GAA provision and the resulting DOF circular were done “within legal bounds” to be able to provide funding for the government’s priority programs.

“It might have been less complicated if the national government simply borrowed money but then, we must consider that as of the end of February 2024, the national government debt was already recorded at P15.8 trillion. Based on a population of 114 million in 2025, every Filipino — young and old, rich and poor, abled and disabled — is indebted in the amount of P139,000 each. This is rather heavy,” said Guevarra.

“It is in this cash-starved context that Congress trained its sight on money that was there but was not being productively utilized,” he added.

The P89.9 billion fund was the “accumulation of three years’ worth of government subsidies” that was not used as of end-2023. Lawmakers also saw this as a mark of “inefficiency” and decided to cut the state insurer from receiving government subsidy altogether in the 2025 GAA.

This is where the government received criticism — why was the excess fund not used to boost PhilHealth’s programs instead? The DOF would later say that “almost 78%” or P46.61 billion of the P60 billion transferred was spent on health-related projects.

But during the second day of oral arguments at the Supreme Court, PhilHealth’s failure to settle claims had been put on the spotlight. Some programs have also yet to be implemented — particularly those under the UHC law, which were affected by the pandemic.

“While tapping GOCC funds instead of imposing new taxes or incurring higher debt may seem fiscally prudent, it should be emphasized that sound public financial management goes beyond effectively managing debt or revenue,” Suzara said on February 5.

“A crucial aspect of fiscal prudence is the proper allocation of resources and this must be evident in the budget.” – Rappler.com

4 weeks ago

23

4 weeks ago

23

![[In This Economy] ‘Is the peace process part of the mandate of PhilHealth?’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2025/02/peace-process-philhealth-february-28-2025.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[In This Economy] Why Marcos is getting high on unprogrammed funds](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-marcos-program-funds-july-19-2024.jpg?fit=449%2C449)